Under normal conditions, each menstrual cycle produces a physiological cystic structure – the follicle – in the ovary, which matures into an egg. After ovulation (the release of an egg from the ovary), the corpus luteum forms in place of the follicle. Such changes are physiological and occur cyclically every month. They are also clearly visible on gynaecological ultrasound and are not considered pathological changes.

However, other types of cysts can form in the ovaries – both benign and malignant. This article will discuss benign ovarian cysts. Some ovarian cysts are linked to menstrual cycle irregularities, while others form on their own when certain ovarian cells don’t develop as they should.

Although these cysts are benign and often asymptomatic, regular monitoring is recommended, with early treatment if necessary. Complications such as cyst rupture or torsion can cause sudden, severe symptoms, and require urgent surgical treatment.

Such cysts depend on the menstrual cycle and occur as a result of its disruption.

They occur when ovulation, or the release of an egg, has not taken place, and the follicle containing the egg continues to grow.

They occur when ovulation has occurred, but fluid continues to accumulate inside the cyst.

Functional cysts rarely cause symptoms and resolve on their own within a few menstrual periods.

The formation of such cysts is independent of the menstrual cycle. Here are the most common types of such cysts.

A cyst that forms from embryonic tissue. They often contain fat, skin, hair, teeth, bone, and cartilage fragments. 0.2–2% of these cysts may be malignant.

A benign ovarian cyst that forms on the surface of the ovary and contains a mucus-like fluid. They can reach very large sizes, which may make it impossible to preserve normal ovarian tissue.

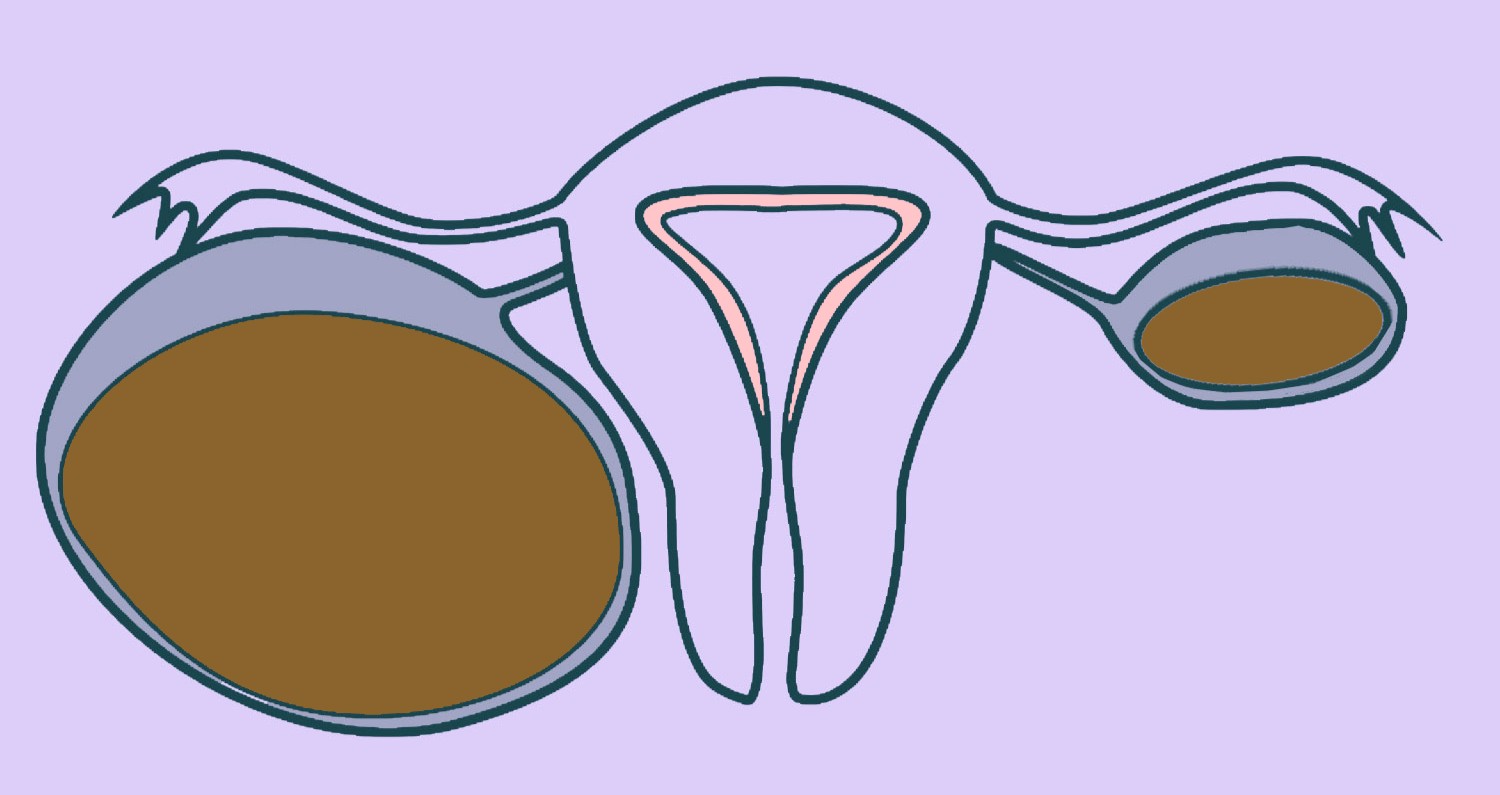

These cysts develop from tissue similar to the uterine lining (endometrium) that grows on the ovary, gradually forming a cyst filled with a chocolate-like fluid. Find more information about endometriotic cysts here.

All benign cysts can grow to a large size and cause significant symptoms, particularly if they undergo torsion, which cuts off the ovary’s blood supply and may necessitate removal if surgery is not performed promptly.

Although the cysts described above are benign and only rarely become malignant, the only definitive way to determine their nature is surgical removal and histological examination under a microscope. If a new ovarian mass develops during menopause, careful evaluation is essential, as the likelihood of malignancy is higher.

Symptoms depend on the size of the cyst and can vary widely. In the case of benign cysts, symptoms will be more pronounced when the cysts are larger in size. The only exception is endometriotic cysts, which, even when small in size, can cause severe symptoms.

Possible symptoms:

If you know you have a cyst and suddenly experience severe pain or vomiting, you should seek emergency medical help immediately.

The potential complications of benign cysts are one of the main reasons for their timely treatment.

The ovary is about 3–4 cm in size and is fixed by ligaments that lead blood vessels to the ovary. In the normal range, as well as with small cysts, the ovary moves freely. When an ovary contains a larger cyst, there is a risk of torsion, where the ovary twists and compresses its blood vessels, cutting off the blood supply. As a result, the ovarian tissue dies.

This can happen on its own or as a result of trauma, for example, during intercourse. The larger the cyst, the greater the risk of rupture. If the cyst ruptures, there is a risk of internal bleeding, and urgent surgical treatment may be needed.

The best way to diagnose ovarian cysts is a gynaecological ultrasound. Ultrasound is a quick and accessible method that not only identifies and measures cyst size but also determines the cyst type with high accuracy. Studies have shown that ultrasound can distinguish benign from malignant cysts with high accuracy by identifying the specific features of each type.

As mentioned above, the vast majority of cysts, especially functional cysts, do not require treatment. They often disappear during 2–3 menstrual cycles. “However, watchful waiting is not always appropriate – it is important to assess both the size and symptoms of the cyst, while also considering the woman’s age.

This approach is appropriate if the cyst is asymptomatic and the ultrasound shows no suspicious features of malignancy. In such cases, a follow-up gynaecological ultrasound is required to monitor changes in the cyst’s size and appearance.

Although this method is often used as a treatment, it is unlikely to reduce the size of existing cysts. Cysts may disappear independently of taking contraceptive medications. Hormonal therapy is a good method for preventing cysts from recurring in women who have them more often.

Surgery is the main treatment for ovarian cysts that cause symptoms, have uncertain characteristics, persist for several months, or when malignancy is suspected. Depending on the cyst’s size, type, and the woman’s age, either conservative (ovary-sparing) or radical treatment may be appropriate.

During the procedure, only the cyst is removed, and the rest of the ovarian tissue is preserved. This approach is possible in cases where no malignancy is suspected.

In this case, the remaining ovarian tissue is removed together with the cyst. This approach is particularly indicated in menopausal women, when malignancy is suspected, when normal ovarian tissue cannot be preserved, or to prevent cyst recurrence.

Most benign ovarian cysts, even large ones, are treated laparoscopically – the entire operation is performed through 3–4 small abdominal incisions. After the cyst is removed or the ovary is detached, the tissue is placed in a special pouch and extracted through a small abdominal incision. Next, the cyst capsule is pierced and the contents suctioned out. This way, the contents of the cyst do not enter the abdominal cavity and cysts larger than 10 cm can be pulled out through a small hole of 1 cm.

CALL US:

+371 26 412 412Consultation with an experienced doctor is the first step towards taking care of your health and well-being.

AIZPILDIET PIETEIKUMA FORMU: